Over my 20 years of experience with Scrum, I’ve observed velocity-driven et capacity-driven Sprint Planning as ways of working when we figure out the amount of work the Development Team can take during a Sprint.

While I believe these practices helped us adopt Scrum by planning our work at each Sprint, I believe we can now go one step further with throughput-driven Sprint Planning.

Before I dive into the details of throughput-driven Sprint Planning, I first want to define the word throughput to avoid any misunderstanding for the rest of this article.

I’ll use the following definition of throughput:

Débit : nombre d'éléments de travail terminés par unité de temps.

Kanban guide for Scrum Teams:

Please note I am not talking about the number of story points per unit of time.

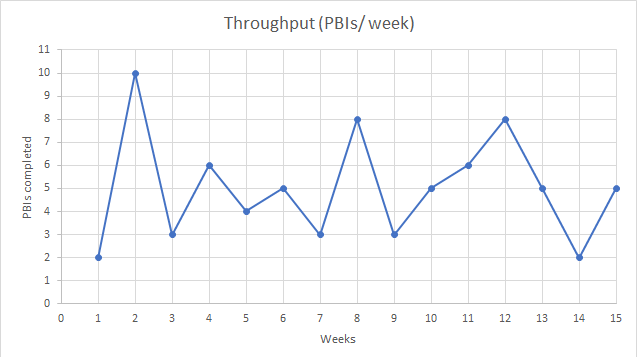

Having defined throughput, let’s imagine a Scrum team running on 2-week sprints. Their Sprint starts on Monday and ends on Friday. The throughput of this Scrum Team for the past 15 weeks is illustrated in the following chart.

On this chart, named a throughput run chart, the Scrum Team completes between 2 and 10 Product Backlog Items (PBIs) per week. If we do the average of the last 15 weeks, we get a trend of 5 completed PBIs per week on average (or 10 PBIs per Sprint).

Also, and this metric is going to be useful later in the article, our Service Level Expectation is 8 days or less, 85% of the time. For now, please keep this metric in mind.

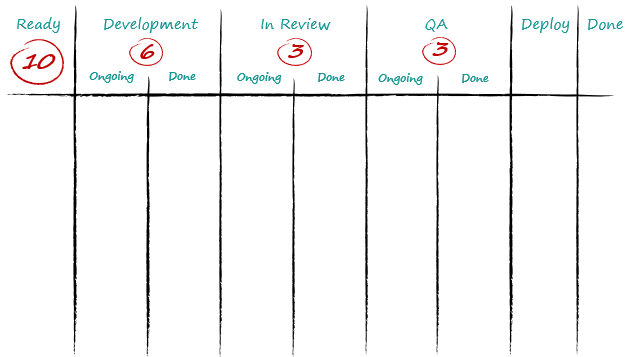

Another thing I want to define is the workflow of the Sprint Backlog used by the Development Team in this imaginary Scrum Team. The Sprint Backlog workflow is the following:

In the Sprint Backlog workflow, they decided to have 3 steps: Development, In Review and QA. There isn’t a WIP limit on the Deploy column because it is easy for the Development Team to catch all PBIs in this column at the end of the day and push them into production.

Developers decide to have sub-columns to make it more transparent when a PBI is completed on each step of the workflow.

The Ready column is the entry point of the Sprint Backlog workflow. At Sprint Planning, we move PBIs from the Product Backlog into this column to inform everyone these are the next items to work on.

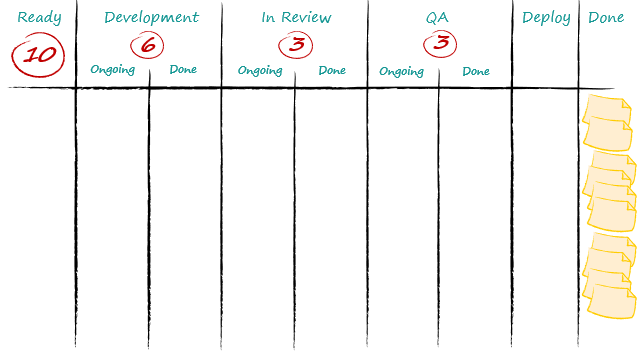

Developers decide to set a WIP limit of 10 on its Ready column based on its throughput run chart. Historically, they can finish 10 PBIs/sprint. Based on this historical data, take around 10 PBIs at Sprint Planning.

Please note that in this Sprint Backlog workflow, developers don’t use tasks to decompose their work. It focuses mainly on delivering Product Backlog Items through this workflow. Decomposing PBIs in tasks is a complimentary practice for them and in this example, developers don’t see a need for them. For all the scenarios listed below, this Sprint Backlog workflow will always show Product Backlog Items moving from left to right.

As we move into a Sprint Planning event, the Development Team forecasts its work accordingly. With the throughput run chart seen above as new input in the Sprint Planning, here are a few scenarios I’ve bumped into when doing throughput-driven Sprint Planning.

Scenario A: No PBIS left in the Sprint Backlog workflow

In our first scenario, developers were not able to move all its PBIs to the Done column on the last day of the Sprint.

During Sprint Planning, as our throughput chart showed initially, developers do 5 items/week. So, we can put around 10 PBIs in for the next Sprint. Over the years, I haven’t been in this situation a lot of times but on the occasions it happens, this is how I would guide my team.

Scenario A.1: There’s nothing in the Sprint Backlog because it’s our first Sprint

I’ve used two approaches in this scenario. In a more project-based context where trust was low, I’ve fallen back on capacity-driven Sprint Planning to estimate the number of PBIs developers could forecast.

In a context where trust is high and risks and/or expectations are low for the results of the first Sprint, developers went with a rough guess based on their gut feeling and adjusted at Sprint 2 based on their learnings in Sprint 1.

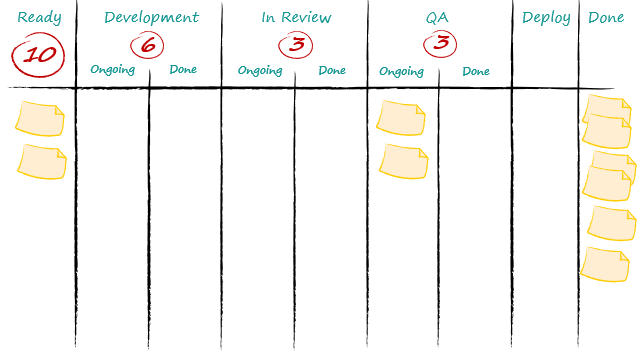

Scenario B: Some items left in the Sprint Backlog workflow

This is the scenario I’ve encountered the most often with my Scrum Teams. Incomplete PBIs are left in the Sprint Backlog when the Sprint finishes.

In the picture above, I have 2 PBIs in the Ready column, 2 PBIs in QA, and 6 in the Done column. To give more context to our example, the 2 PBIs in Ready are not related to the sprint goal of the previous Sprint.

Two options lie in front of us at Sprint Planning:

- Option 1: We can put less than 10 PBIs in the Ready column. Looking at the Sprint backlog workflow above, we see the development team completed 6 PBIs in their sprint. This lowers their historical average throughput. If the Development Team feels this will be their new “norm”, we can put less than 10 PBIs in the Ready column

- Option 2: We can fill up the Ready column with up to 10 items. Developers want to keep going at that pace even though they delivered 6 PBIs in this Sprint. They consider a series of unpredictable events that slowed them down during the Sprint. They don’t believe they will face the same issues soon and can get back on track.

Scenario B.1: Team members will be on paid time off (PTO) during the Sprint

I use ratios to calculate the amount of PBIs we can take. For example, if a Development Team of 6 people completes 5 items per week, and two team members will be away for a week during the Sprint, they can reduce their throughput to 3 or 4 PBIs per week.

Scenario B.2: The next PBIs to go into the Sprint Backlog are quite small

For example, the Product Owner only has a list of bugs she wants to fix in the Sprint. They are all around 1 day of work or less. In this situation, I find there’s nothing wrong with going over our WIP Limit on the Ready column. You might want to keep your current WIP Limit at 10 for the Ready column as value-added PBIs (Ex: user stories) are scheduled after this bug-fixing sprint.

The size of the PBIs

If I am to use throughput to forecast the amount of work in a Sprint, what should their size be? How do I size my PBIs? I often hear these questions when I bring up throughput-driven Sprint Planning. While I find story points were great for limiting the size of an item in our Sprint, I believe story points are also a limitation when it comes to throughput-driven Sprint Planning.

A simple answer I heard from the questions above is “PBIs should always be around the same size when going in the Sprint Backlog”. I never felt right with this answer as it forces our Product Owner to resize or bundle stories. I don’t believe our Product Owner should adapt his work to fit this answer.

I found a great alternative to story points a few years ago when I stumbled on Daniel Vacanti book Actionable Agile – Metrics for predictability. In chapter 12 of his book, Vacanti explains how we perform a “right-size” check on the PBI we are about to plan. This check is on the Service Level Expectation (SLE) that either your data tells you or one that you have chosen if you don’t have enough data.

According to the Kanban Guide for Scrum teams, the definition of Service Level Expectation is:

Forecasts how long it should take a given item to flow from start to finish within the Scrum Team’s workflow. […] The SLE itself has two parts: a period of elapsed days and a probability associated with that period (e.g., 85% of work items should be finished in eight days or less)

Kanban Guide for Scrum teams

If we go back to the beginning of our article where we defined our imaginary Scrum Team, it stated the SLE was 8 days or less, 85% of the time. By doing throughput-driven Sprint Planning, each item that you add to your Sprint Backlog should have a quick question in the form of “Can this PBI be done in 8 days or less?”

To quote Daniel Vacanti from his book:

The length of this conversation should be measured in seconds. Seriously, seconds. Remember, at this point we do not care if we think this item is going to take exactly five days or nine days or 8.247 days. We are not interested in that type of precision as it is impossible to attain that upfront. We also do not care what this particular relative complexity is compared to the other items. The only thing we do care about is we think we can get it done in 14 days or less. If the answer to that question is yes, then the conversation is over and the item is pulled [in the sprint backlog]. If the answer is no, then maybe the team goes off and thinks about how to break it up, or change the fidelity, or spike it to get more information

Actionable Agile – Metrics for predictability, chapter 12

Instead of using story points and velocity to decide if a PBI is going into the Sprint Backlog, we use the Development Team Service Level Expectation (SLE) to make this decision.

Scenario C: PBIs close to the SLE

As we are moving new PBIs into the Ready column at sprint planning, we realize all of them are close to the sprint backlog workflow SLE. Developers indicate how the new PBIs are around 7, 8 or 9 days of work, thus being close to the SLE of 8 days or less, 85 % of the time. After a conversation, developers can decide if they want to move forward knowing this or it might be sound to take a little less than 10 PBIs if all of them are close to the SLE.

Scenario C.1: PBIs small to the SLE

On the other hand, if all of the PBIs we are moving into the Ready column are worth a day or two of work, thus being far from the SLE, it might make more sense to add a few additional PBIs knowing they will flow fast through the Sprint Backlog workflow. We’ve already covered an edge case of this above in Scenario B.2 where the work for the Sprint was solely a list of bugs to fix.

To sum it up

I believe throughput-driven Sprint Planning is an alternative to the mainstream approaches known to the agile community. I find its strength is the use of historical data and less about estimation and relative sizing. Historical data is easy to capture, to teach, and to use.

I’ve been teaching the Professional Scrum with Kanban (PSK) class for the last 6 years now where we address this on day 2. Participants are surprised at how we can reduce our time in meetings with this new approach. It’s more time given back for developers to do what they do best. It’s more efficient time spent on valuable conversation instead of arguing if it’s a 3 points or 2 points.

It’s a win-win for our profession and the customers we help build solutions for.